The potential environmental benefits are such that scaling up production is a worthy challenge. But there are downsides, too.

A few years ago, I hosted Science To Go, a Discovery Channel series on food. We travelled to Chicago to investigate deep-dish pizza, to Battle Creek, Mich., to explore the history of breakfast cereal, and to the Cornfest in Taber, Alta. The most impactive episode for me turned out to be the one in which we focused on meat production. We visited poultry farms where thousands of chickens clucked in close confinement and giant beef processing plants where cows walked up the “stairway to heaven,” as workers called it, and exited hours later packaged as steaks and burgers. 100 Mm Petri Dish

Subscribe now to read the latest news in your city and across Canada.

Subscribe now to read the latest news in your city and across Canada.

Create an account or sign in to continue with your reading experience.

Don't have an account? Create Account

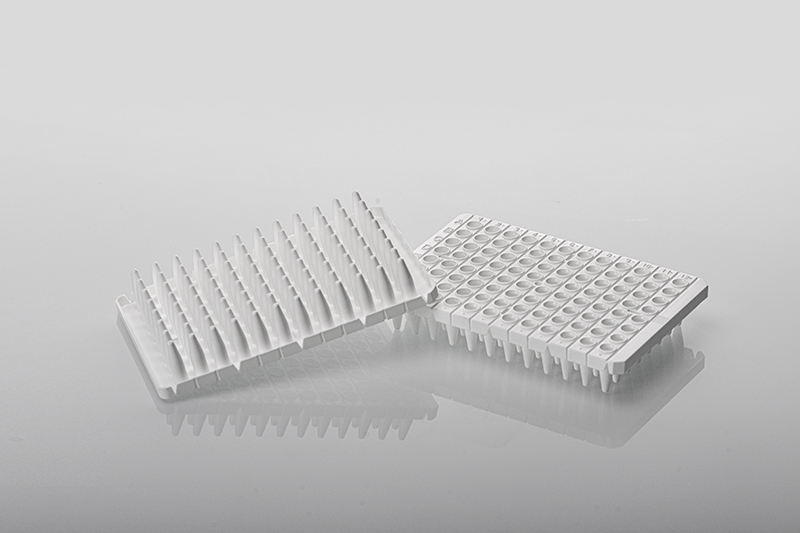

Although we witnessed some disturbing scenes, neither the crew nor I stopped eating meat. Burgers, steaks and barbecue chicken were too ingrained in our lives. I didn’t give much thought to the less-than-appetizing practice of raising animals so that we could slaughter and eat them, until 2013 when news from Maastricht University in the Netherlands made headlines. Dr. Mark Post had produced a hamburger that did not come from a slaughtered cow. It was made from harvesting cells cultured for two years in stacks of Petri dishes. This was still an animal product in the sense that the original cells came from a biopsy taken from the shoulder of a cow. And the burger came with a hefty price of $325,000!

The two food critics who had the privilege of tasting the burger gave it a pass for taste but noted its lack of juiciness, since it was made from muscle cells and contained no fat. Animal welfare activists and environmentalists celebrated the experiment while cattle ranchers complained that the meaning of meat was being hijacked since the very definition of meat is that it comes from the flesh of an animal.

Get the latest headlines, breaking news and columns.

By signing up you consent to receive the above newsletter from Postmedia Network Inc.

A welcome email is on its way. If you don't see it, please check your junk folder.

The next issue of Headline News will soon be in your inbox.

We encountered an issue signing you up. Please try again

Culturing cells in a lab traces back to 1907 when American zoologist Ross Granville Harrison isolated nerve cells from a frog embryo and found that they multiplied when immersed in lymph fluid. The method was improved by French surgeon Alexis Carrel who substituted blood plasma for lymph and managed to keep cells taken from chick embryo hearts alive and growing for years. That claim, however, was challenged by American microbiologist Leonard Hayflick who maintained that normal cells have a finite proliferative capacity. Carrel, Hayflick maintained, must have introduced some living cells via the plasma medium that was constantly added to the culture.

By the time Post made history by serving the most expensive dish ever produced, many of the details of tissue culture had been worked out by researchers. They had investigated different cell lines, including stem cells that can develop into muscle or fat cells, and also identified the specific amino acids, sugars, vitamins, minerals and growth factors that cells need to multiply. At that point, a number of startups got into the game hoping to eventually commercialize cultured meat.

The first problem was nomenclature. What do you call the newfangled product? Opinion was that “lab-grown meat” and “in vitro meat” would scare consumers. “Cultured meat,” “cell-based meat” and “clean meat” were considered but consensus seems to be that “cell-cultivated meat” is what will fly. And it took off in 2020 in Singapore, the first country to approve the sale of such meat. A prediction made nine decades earlier had come true!

Who was the seer who made that prediction? None other than Winston Churchill, who in 1931 prophesied that in the future “we shall escape the absurdity of growing a whole chicken in order to eat the breast or wing, by growing these parts separately under a suitable medium.” The American company Good Meat made that happen, although it did not exactly grow wings and breasts, but a product that is more like ground meat. This, however, can be compacted into filets, much as is done with chicken nuggets. “Phyllo puff pastry with cultured chicken and black bean purée” was the version served in Singapore at Restaurant 1880, which has a reputation for innovation and social consciousness. The chicken was priced at a fraction of the cost of its production.

For now, cost is a major issue. The nutrients are expensive, as are the large stainless-steel vessels needed to culture the cells. Those vessels, called bioreactors, can be seen through a glass wall at The Chicken, in Tel Aviv, the second restaurant in the world to serve cultured chicken. It belongs to the Israeli company SuperMeat, and serves crispy chicken filet on a semi-sweet brioche bun. Another Israeli company, Aleph Farms, is more ambitious and is on the verge of producing a steak by coaxing stem cells to differentiate into muscle, fat and connective tissue cells that then grow on a plant-based microscopic scaffolding that replicates the muscle fibres of conventional meat.

The U.S. is the latest country to hop on the bandwagon, with the Food and Drug Administration and the Department of Agriculture having approved cultured meat. Bar Crenn, a high-end restaurant in San Francisco will start selling “cell-cultivated meat” made by the Upside Company, and the China Chilcano restaurant in Washington is set to serve Good Meat’s chicken.

For now, cultured meat is more of a curiosity since it cannot yet be produced on a large scale. However, the potential environmental benefits are such that scaling up production is a worthy challenge. Animal agriculture accounts for about 15 per cent of all greenhouse gas emissions, with beef being by far the greatest culprit. Most of the corn and soybean grown go to feeding animals, and large tracts of land end up being deforested to grow these crops and to make room for feedlots. Far more water is needed to raise animals than to make cultured meat, and the latter never requires the use of antibiotics. Furthermore, animals are not an efficient way to meet our protein needs. For example, it takes nine calories of feed to get one calorie of meat from a chicken.

But cultured meat has its issues as well. A great deal of energy is needed to run the bioreactors, some consumers won’t make peace with what they call a “Frankenfood,” and the taste of a Black Angus steak is unlikely to be challenged. And then there is the question of why cultured meat is needed. Why not just promote a far cheaper diet that features plant proteins?

As far as safety goes, I would not be chicken to try “cell-cultivated” chicken.

Joe Schwarcz is director of McGill University’s Office for Science & Society (mcgill.ca/oss). He hosts The Dr. Joe Show on CJAD Radio 800 AM every Sunday from 3 to 4 p.m.

Postmedia is committed to maintaining a lively but civil forum for discussion and encourage all readers to share their views on our articles. Comments may take up to an hour for moderation before appearing on the site. We ask you to keep your comments relevant and respectful. We have enabled email notifications—you will now receive an email if you receive a reply to your comment, there is an update to a comment thread you follow or if a user you follow comments. Visit our Community Guidelines for more information and details on how to adjust your email settings.

365 Bloor Street East, Toronto, Ontario, M4W 3L4

© 2023 Montreal Gazette, a division of Postmedia Network Inc. All rights reserved. Unauthorized distribution, transmission or republication strictly prohibited.

Falcon Tube 50ml This website uses cookies to personalize your content (including ads), and allows us to analyze our traffic. Read more about cookies here. By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Terms of Service and Privacy Policy.